More studies are needed to unveil the mechanisms behind this interaction, which may allow, in the future, clinicians and educators to consider sleep in the effort of regulating glycemic control. Our results support the hypothesis of an interaction between sleep parameters and T1DM, where the glycemic control plays an important role.

#Actimeter sleep full

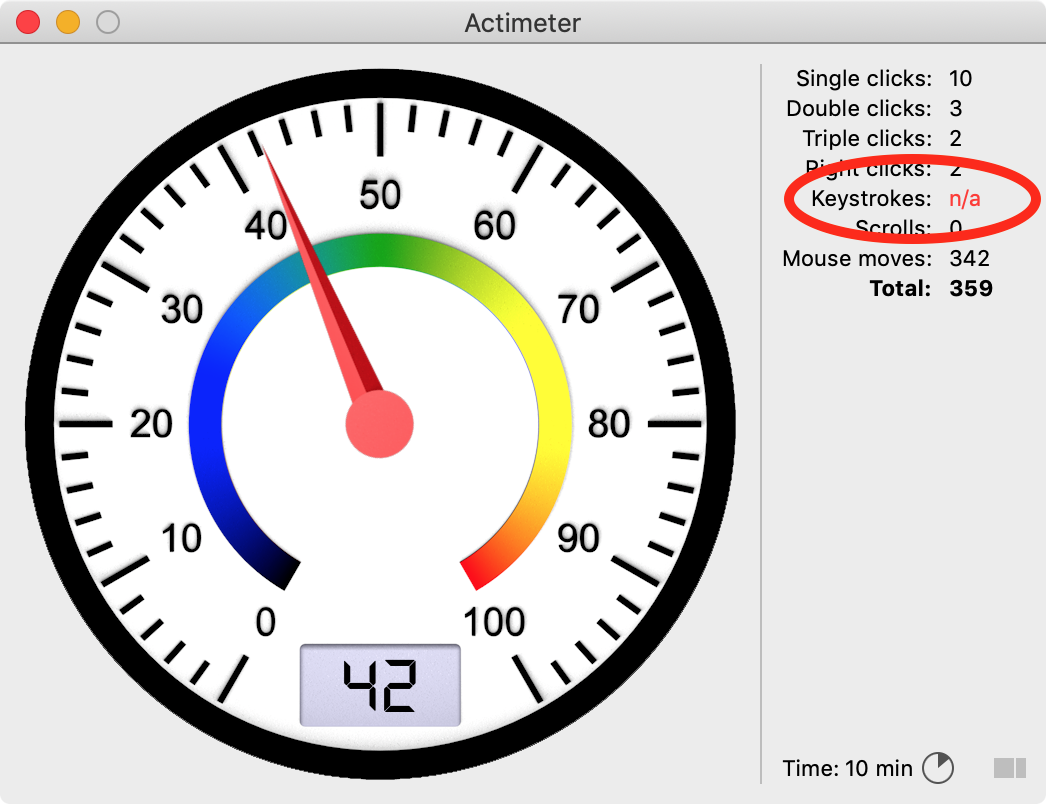

Among T1DM, glycemic variability (SD) was positively correlated with sleep latency (r = 0.6525, p = 0.0033) full awakening index and arousal index were positively correlated with A1C (r = 0.6544, p = 0.0081 and r = 0.5680, p = 0.0272, respectively) and mean glycemia values were negatively correlated with sleep quality in T1DM individuals with better glycemic control (mean glycemia < 154 mg/dL). Glycemic control in T1DM individuals was evaluated through: A1C, home fingertip glucometer for 10 days (concomitant with the sleep diary and actimeter), and CGM or concomitant with continuous glucose monitoring (during the polysomnography night).Ĭomparing with the control group, individuals with diabetes presented more pronounced sleep extension from weekdays to weekends than control subjects (p = 0.0303). The following instruments used to evaluate sleep: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, sleep diaries, actimeters, and polysomnography in a Sleep Lab.

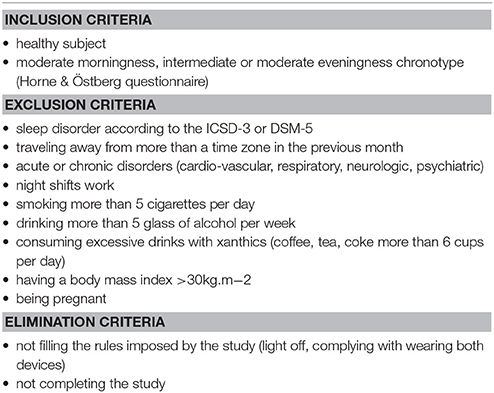

These findings indicate that chronotype might be modified during remission, which should be further investigated in longitudinal studies.Īdolescent depression Chronotype Light exposure MCTQ Sleep Wrist actigraphy.Our aim in the present study was to elucidate how type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and sleep parameters interact, which was rarely evaluated up to the moment.Įighteen T1DM subjects without chronic complications, and 9 control subjects, matched for age and BMI, were studied. Additionally, light exposure in remitted patients was significantly higher, but this finding was mediated by living in a rural environment. However, patients with remitted depression slept significantly longer on work-free days and reported a worse subjective sleep quality than controls. To measure a person’s sleep, researchers have always relied on costly and time-consuming approaches that could only be used in a sleep lab. In our sample, adolescents with remitted depression showed similar chronotypes and similar amounts of social jetlag compared to controls. Summary: A simple actimeter device is helping researchers better understand sleep duration and quality in humans. Given the potentially mediating effect of light on chronotype and depressive symptoms, we measured light exposure with a light sensor on the actimeter. For this purpose, we assessed chronotype and social jetlag with the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (MCTQ), subjective sleep quality with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and used continuous wrist-actimetry over 31 consecutive days to determine objective sleep timing. In this study, we investigated whether adolescents with remitted depression differ from healthy controls in terms of chronotype, social jetlag and other sleep-related variables.

A late chronotype as well as a misalignment between internal time and external time such as social jetlag has been shown to be associated with depressive symptoms in adults.

Chronotype is mostly regulated by the circadian clock that synchronises the internal time of the body with the external light dark cycle. One important sleep variable is self-selected sleep timing, which is also referred to as chronotype. The relationship between sleep and adolescent depression is much discussed, but still not fully understood.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)